Canada’s wealth could face a cataclysmic future

By Keith Brown

CFP, CLU, CH.F.C, FEA, CExP™, TEP Business Family Advisor

One horseman is here already. Two are just around the corner. The fourth looms on the horizon.

As horseman #1, AKA COVID-19, continues to gallop across the country, the long-term economic and financial havoc it will wreak is likely to be beyond what any of us can predict.

In response, the Trudeau government is unleashing horseman #2; anchor-less spending, and, along with it, horseman #3; a plan to rebuild the economy “better”.

All this while horseman #4, the implementation of a wealth tax, looms on the horizon.

The havoc COVID-19 is causing is plain to see. That may not be the case for the other three horsemen, but there is still time to rein them in if the right decisions are made – by all of us.

Anchor-less spending – Horseman #2

In September, the Conference Board of Canada reported, “The crisis has stretched the limits of federal and provincial government finances. A return to austerity is in the cards…”

Or not. In late October, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stated that Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland’s promised update on federal finances won’t have a fiscal anchor to keep spending from spiraling out of control.

In normal times, spending is constrained by fiscal anchors including the size of the deficit and maintaining a low debt-to-GDP ratio. These anchors ensure governments exercise some discipline when they roll out their spending plans.

Without an anchor, drifting finances could mean the country will suffer for years to come. The Minister of Finance has since referred to future fiscal guardrails, but has not offered enough detail to provide assurance that they will be effective.

In June, the Fitch Rating service cited “significant fiscal deterioration in 2020” as a key factor in downgrading Canada’s from AAA to ‘AA+’/Stable. Credit ratings are the foundation of confidence in the Canadian economy. The unprecedented deficit we are heading towards – estimated to be above 21% of GDP in 2020 – is significantly higher than the 16.1% of GDP estimated at the time of the downgrade.

The Conference Board of Canada forecasts Canada’s pace of economic recovery will flatten, if not stall. With this in mind, a critical question has to be asked: Is the money currently being spent actually going to help the country recover from the aftermath of the COVID-19 induced financial crisis?

One wonders about this when, despite the loss of jobs, the Conference Board of Canada is predicting aggregate household real disposable income to post a record gain in 2020, up more than 9 per cent.

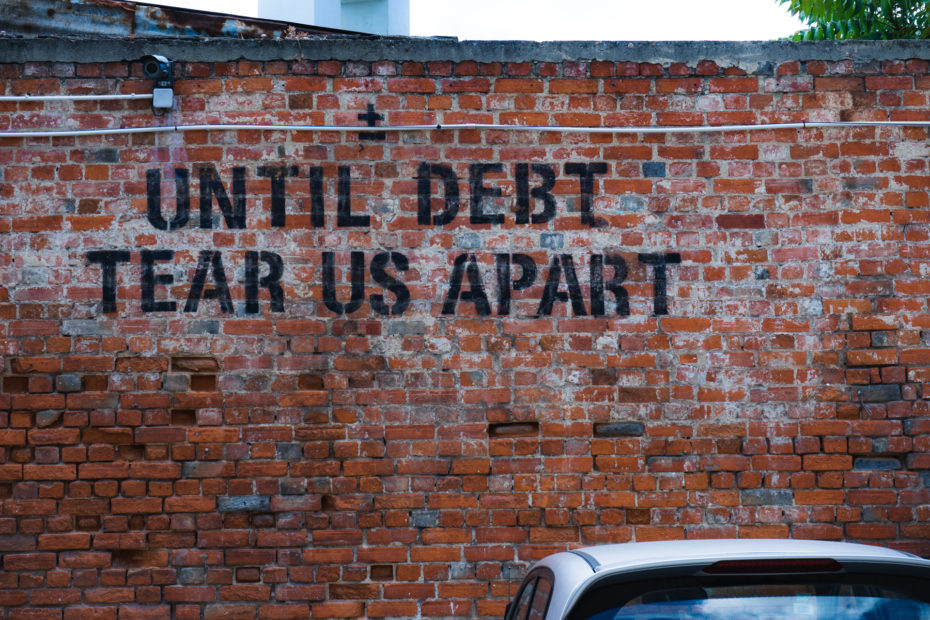

Currently, low interest rates make it easy for governments to borrow money. It’s not surprising that the federal debt has risen from $685 billion in 2018 to an estimated $1.2 trillion this year. But, instead of spending on infrastructure and supporting business growth, too much of the spending is merely boosting consumption. What’s going to happen when interest rates start to rise? The old adage, borrowed money is easy to acquire but hard to retire, has never been truer.

Rebuilding the economy “back better” – Horseman #3

“We are asking Canadians to embark on an entirely different direction as a government,” Trudeau told a CBC interviewer in September. “We are going to rebuild the Canadian economy in a way that was better than before.”

In his throne speech later that month, Trudeau gave Canadians a first look at how he defines “better”. And, in my estimation, there is very little in the definition that directly improves the economy, unless of course you believe spending, spending, spending is sound strategy.

There is nothing wrong with any of his priorities. They include making the Canadian economy more environmentally friendly, spending to support and protect vulnerable people, extra money for child care to empower working women, and initiatives that address systemic racism.

However, a recent Fraser Institute study suggested Ottawa has directed billions of dollars to poorly targeted assistance. One example is the $2.5 billion given to seniors who qualify for Old Age Security, many of whom said they didn’t need the money.

Writing in the National Post, John Ivison said, “Freeland’s attempt to close the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ risks creating a new class of Canadians – the ‘have-not-paid-fors.’” So, while Finance Minister Freeland remains vague about what this course of action will mean for Canada’s future, one thing is for certain, there is a fine line between enabling and empowering… and perhaps that line has already been crossed.

What’s missing in the Liberal’s “better” vision is the means to pay for it. Without a foundational shift in thinking that puts the long-term competitiveness of all Canadian businesses, , we risk building a financial house of cards.

Wealth Tax – Horseman #4

In the September Speech from the Throne, the government said a tax on the “extreme wealth inequality” in Canada was being considered.

Then, in early November, Peter Julian, the NDP member of parliament for New Westminster-Burnaby, echoed this theme of inequality with this motion:

“…given that since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadian billionaires are $37 billion richer while the most vulnerable are struggling, the House calls upon the government to put in place a new one percent tax on wealth over $20 million and an excess profit tax on big corporations that have been profiteering from the pandemic…”

Even though the motion failed 292 to 27, it is a sign of the times. Philip Cross, a Fraser Institute Senior Fellow, wrote in mid-October that, “The myth that inequality reached extreme levels is an example of a narrative from the United States distorting a policy debate in Canada.”

Cross is firmly of the opinion that a wealth tax would be a mistake. First, it is simply not justified because wealth inequality is not increasing in Canada. He cites Statistics Canada data that shows “wealth held by the lowest three income quintiles rose more than that held by the highest two quintiles, raising their share of wealth from 27.1% in 2010 to 29.5% in 2019.”

Contrary to a general misconception given credibility by Ottawa, Cross says the increase in wealth was led by younger generations. “The wealth of baby boomers rose by 64.6% between 2010 and 2019, while for Generation X it increased 133.9% and Millennials posted a 465.5% gain.”

Cross says, that despite the growth in equality, because half of the accumulated wealth in Canada is held by older people, “…a tax on wealth can easily morph into a tax on age.”

It’s more than that. The wealth tax experiment has been tried many times in Europe with most countries gaining little in actual revenue while finding it nearly impossible to administer. Think about the baby boomers who hold more than half of the nation’s wealth; for the most part, their assets are pensions, retirement savings, and real estate.

Real estate owners, especially those whose income comes from fixed rents, will be among the first victims of the fourth horseman of the taxpocalypse. That’s because the value of their assets has risen at twice the rate of their incomes since around 1997. And, as this disparate rate of growth widens, they simply will not have the cash to pay this form of tax. They will be forced to sell off their property or defer the tax until the ownership is transferred to the next generation… who will then have to sell off the property!

Despite past failures, Britain too is considering a wealth tax. It is actively working to figure out how to make it as effective – read “unavoidable” – as possible. Considering the close ties between the Bank of England and our Bank of Canada, this could be a harbinger of what will happen here.

Can We Avoid a Taxpocalypse?

Yes, we can. But it has to start with a government intent on finding ways to get people and companies to invest the billions of dollars currently sitting on the sidelines.

We have to stop letting the government damage our collective self-sufficiency. As a collection of individuals and a community of companies, we must re-evaluate our increasing willingness to take government money. What does it say about us when we take money we don’t really need? When we accumulate profits that are not real? When we are complicit in a wildly reckless debt increase of 50% in one year?

We can avoid the taxpocalypse by taking responsibility for our individual actions and by helping businesses become stronger, more competitive, and better able to lead the post-COVID economic recovery.

If we don’t, and in the next five years interest rates increase dramatically, or Canada suffers another financial meltdown, we will be buried in irreversible debt and the taxpocalypse will surely be upon us.

Nicely written. Makes a lot of logical sense.

All the best for the new year